On October 25, the United States Air Force Academy announced that the words “So Help Me God” would be optional when cadets recite the Honor Oath. Established in 1984, the cadet Honor Oath reads:

We will not lie, steal or cheat, nor tolerate among us anyone who does. Furthermore, I resolve to do my duty and to live honorably, so help me God.

Photo By Dennis Rogers (US Air Force Public Affairs)

In an official press release Lt. Gen. Michelle D. Johnson said:

Here at the Academy, we work to build a culture of dignity and respect, and that respect includes the ability of our cadets, Airmen and civilian Airmen to freely practice and exercise their religious preference — or not…In the spirit of respect, cadets may or may not choose to finish the Honor Oath with ‘So help me God.’

Since that October announcement several media outlets and blogs mistakenly reported that it was the Air Force itself who had made “so help me God” optional. Currently all branches of the United States Armed Forces use an official Enlistment Oath which ends with that very same phrase. According to congressional law, this oath must be recited before serving in the military.

While there may be no legal allowance for religious difference, there is apparently some leeway in practice. Administrating officials have been known to permit the omission of the final phrase. In fact an official U.S. Army document states: “The words ‘So help me God’ may be omitted for persons who desire to affirm rather than to swear to the oath.”

Looking beyond the Military, the word “God” permeates a great deal of American social space. In this supposedly post-Christian society, the word “God” becomes increasingly cumbersome in secular settings; its use more glaring and far more difficult to digest within a pluralistic environment. Regardless, “God” is ever-present in both the American vernacular and United States legalese – from idioms to oaths.

Just this past week the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) debated the constitutionality of prayer before government meetings. Ironically SCOTUS opened the session with its usual phrase: “God save the United States and this Honorable Court.”

Photo By Jarek Tuszynski (Jarekt) (Own work) via WikiCommons

As with the Military the Justice department requires its judges, justices, and laywers to take an oath ending with the phrase “So Help Me God.” The lawyers’ oath reads in part:

Do you solemnly swear or solemnly and sincerely affirm, as the case may be, that you will do nothing dishonest, and will not knowingly allow anything dishonest to be done in court …. so help you God or upon penalty of perjury…

Unlike that of Justice Department, the general lawyer’s oath is devoid of religious language. However a few states, such as South Carolina, have opted to include that popular ending phrase.

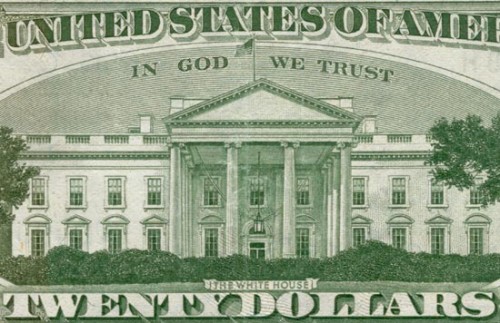

The use of the word “God” is not limited to legal oaths and appears in many very public arenas. All U.S. currency is inscribed with the words “In God We Trust.” According to the U.S. Treasury, the stress of Civil War led to a marked increase in religiosity. As a result the government received multiple requests asking for “God” to be acknowledged on our national money. One such letter reads:

You are probably a Christian… Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past that we were a heathen nation? What I propose is that instead of the goddess of liberty we shall have next inside the 13 stars a ring inscribed with the words PERPETUAL UNION; within the ring the allseeing eye, crowned with a halo; beneath this eye the American flag, bearing in its field stars equal to the number of the States united; in the folds of the bars the words GOD, LIBERTY, LAW.

In 1864 the U.S. Mint began printing coins etched with the phrase “In God We Trust.” Over time and with the necessary acts of Congress, these words began to appear on all U.S. coins. Finally in 1956 Congress made it mandatory for the phrase to be printed on all money and, if that wasn’t enough, the phrase became the country’s motto. During the 1950s the U.S. was paralyzed by a fear of a communist take-over and as a result clung tightly to a conservative sensibility.

Interestingly, the words “Under God” which are nested within the Pledge of Allegiance followed a similar historical pattern. The pledge itself was first adopted right after the Civil War in an effort to unite a broken nation. In 1953 the Knights of Columbus lobbied to add the words “Under God” in order to combat the “godless communism.” The addition was made official in 1954.

Since their inception both phrases have been legally challenged again and again. However the courts generally dismissed these cases. In September atheists lost yet another lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the public use of “In God We Trust.” According to AP U.S. District Court Judge Harold Baer Jr. , “the Supreme Court has repeatedly assumed the motto’s secular purpose and effect.” This summarizes the general position of the courts. Despite the religious nature of the word “God,” these phrases are considered secular and, consequently, do not put a “substantial burden” on any citizen.

One term that has never been legally challenged is the phrase “act of God” which appears most frequently in legal settings or the insurance business. An “act of God” is a “natural phenomena whose effects could not be prevented by the exercise of reasonable care and foresight.” Here is another situation where we are to accept “the motto’s secular purpose and effect” despite the religious verbiage. Is this problematic? To many Pagans, tornado damage might be called “an act of the Goddess” or to an atheist, “wind.” Should our public communication reflect these differences?

Pledge Of Allegiance 1899

Language can be very interesting in that it tells the story of social change through the “colloquial residue” left by ages long gone. Think of all the idioms that are commonly tossed around such as “God Bless You,” “God Only Knows,” “God-Given Right,” “Swear to God,” “For God’s sake” and of course all of those colorful phrases using “Jesus.”

Most of these colloquialisms have indeed lost their religious meaning. When someone yells “God Damn it!” after stubbing a toe on a chair, he isn’t expecting the settee to spend an eternity in Hell. One of my favorite examples is the phrase: “come-to-Jesus meeting.” This is a synonym for the word “intervention” – of whatever sort. While the secular meaning is quite clear, the undertones still remain. The phrase clings to its origins bringing with it the story of a culture’s religious heritage.

Need another example? The full lyrics to the Star Spangled Banner include the phrase, “And this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust.’” Before the song became our official national anthem in 1931, the most popular patriotic song was “God Bless America.” As we continue move into this post-Christian world, the courts will continue to face challenges to any and all religious language used within the public sector – money, oaths, pledges and perhaps even the singing of these patriotic songs.

Congressman Pete Olson. Photo courtesy of Flickr’s euthman

On October 30, Republican Texas Congressmen Sam Johnson and Pete Olson have introduced bill H.R. 3416 in response to the Air Force Academy’s Oath change. If passed, the bill would require Congressional approval for all oath changes. Congressman Olson laments,

It was disheartening to see the Air Force Academy succumb to anti-religious zealotry … The military personnel being trained to defend the rights of Americans should be able to exercise their religious convictions by affirming their oath with so help me God.

The Congressmen must have missed the word “optional” in the Air Force Academy’s release.

But the question still remains: Can there ever truly be a secular use of the word “God?” While their use today may indeed feel secular, does the residual religiosity subvert the growth of a peaceful and respectful multi-culturalism within the public sphere? Does the argument have to be all or nothing, God or Godless? Can our country reach a comfort level within its social pluralism that allows for variations like “so help me Goddess.” Only time and the courts will tell.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Ironically, a requirement that sworn oaths include the name of “God” means that people who do not believe in “God” (or in that particular “God”), but take the oath anyway because they have no other choice, are technically being forced to commit perjury — they are implicitly affirming the truth of something which they believe to be false.

I wonder what would happen if a Pagan substituted “Thor” or “Osiris” for “God” when making this oath, or if a Muslim substituted “Allah”, or Hindus, “Shiva”.

I received my first ever jury duty summons over the summer, and, when we were sworn in as jurors, I was impressed that the person overseeing the oath made it clear that swearing on a Bible and any God language were optional for that oath. On the other hand, when I was chosen for the jury on a murder trial and spent the next week watching witnesses being required to swear an oath ending with ‘so help me God’ with their hand on a Bible, I was a little disheartened. Those may have been optional there, as well, but both the wording and the use of the Bible were offered as if a requirement.

Can the word “god” be secular? I imagine sub-intellects may use it as such, but no, it really can’t. It is all about the basic definition.

Really, I think the closest you can get to a secular usage would be in the form of OMG and even that doesn’t entirely fit.

I always ask “Which god?” when someone makes that exclamation.

No, the word “God” can never be secular. Judicial attempts to square this circle are trying to bridge two stools: The utter lack of meaning the word has in these contexts for most people, and the steep political price for trying to revoke the inherent privilege of the self-anointed Godly few who care about it. It is an attempt to salve the privileged by labeling “secular” the aforementioned lack of meaning.

Something to remember about “God damn it”: the original meaning of the phrase “to damn” is not “to send to hell,” but instead “to forget.” So, when someone stubs their toe on something and says “God(s) damn it,” they’re saying “I wish that God would forget that unfortunate thing just happened, thus making it not happen/exist.” It’s an important subtlety that has become lost over the years, unfortunately…

There are some interpretations of “Hell” that suggest that, rather than being a place of torture, it is merely being outside the presence of “God” which would (I suppose) amount to much the same thing.

True enough…

I’m afraid you may be mistaken about that, Sufenas. Damn > Lat. damnare: to condemn, sentence.

I mis-spoke; you’re correct.

The Latin context in which I have seen it most used is the damnatio memoriae that was done to many “bad” emperors (e.g. Elagabulus in particular), and since “condemnation to memory” doesn’t quite translate that term with the correct valence (and it would be more like “condemn from memory”), I was therefore misreading it based on that particular usage.

I’m sorry to burst any bubbles, but this has been a settled matter since 1787. The Constitution requires giving a secular option for oaths like the Air Force Academy one (not to mention jury duty, being sworn into office, etc.). Any governmental entity refusing to allow such an option would be violating constitutional law.

Constitution of the United States, Article VI, paragraph three: “The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers,both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

No, there isn’t a secular use or purpose for a religious oath, nor for the word “God”. That is why the Founders didn’t require oaths of office. The option of oath or affirmation was intended to allow the solemn pledge to be made in the way that was most binding and meaningful to the person taking it, without privileging one over the other.

Been thinking on this and, really, it is the word ‘secular’ that has the problem, not the word ‘god’.

There is a move to make the word ‘secular’ mean “Christo-normative”, and that is simply unacceptable anywhere.