This week my column comes to you from the sandy shores of the Florida coast. For the last ten years, I’ve celebrated the Summer Solstice in the sunshine state with many other visiting “sun worshippers.” As I’m taking a break from (sub)urban life, I figured that I’d take The Wild Hunt with me on vacation.

No. I’m not going to make you sit through a slide show of vacation photos. I would like to take you on a journey to explore one of paradise’s most iconic symbols – the Hula.

I have always loved dance – the sacred, the ethnic, the purely artistic and even the raise-the-roof, pump-up-the-jam variety. Movement is powerful and magical in all forms. But up until this week, I never really stopped to consider the Hula – the traditional dance of Polynesian culture. It is very hard to take a dance seriously whose imagery has found a comfortable home in the plastic form of a bobbling dashboard ornament. For many people, the traditional Hawaiian dance is never really explored outside of a tourist setting, at luau parties, or on TV. I speculate that my own introduction to Hula was through reruns of The Brady Bunch Hawaii Bound (1972).

Despite its place in pop culture, the Hula has a serious and sacred history that tells the story of a culture and a people. While its precise origin can’t be historically pinpointed, the Hula is indeed a cultural product of the ancient Polynesian societies that thrived on the islands in the Southern Pacific Ocean. By some mythical accounts, Laka, the forest Goddess, gave birth to the celebratory Hula dance. She is still considered the patron Goddess of the dance. In other stories, Hula was a gift given to the Goddess Pele by her sister Hi’aka. And other stories abound…

In all cases, Hula was a dance of the Goddess and of nature. Traditional motions and movements mirrored natural rhythms such as the fluid, hypnotic flow of the ocean or tumultuous, stormy skies. The dance expressed and told the stories of the surrounding island worlds.

As a sacred and respected dance Hula was used for a multitude of purposes. It was a way by which these ancient people could pass down their traditions, their history, and their religion to the coming generations. It was used to honor deity, local chiefs and important community members. Hula was performed in religious ceremonies, festivals, funerals, births, and weddings. In 1778, Captain Cook wrote:

Their dances are prefaced with a slow, solemn song, in which all the party join, moving their legs, and gently striking their breasts in a manner and with attitudes that are perfectly easy and graceful. (From Hawaiian History)

By the 1800s Protestant missionaries began to settle in the Hawaiian Islands. Their reaction to the traditional dance was quite different from Captain Cook’s. They considered it sinful – a “heathen” dance of a “pagan” culture.* One missionary wrote:

The whole arrangement and process of their old hulas were designed to promote lasciviousnous [sic], and of course the practice of them could not flourish in modest communities. They had been interwoven too with their superstitions, and made subservient to the honor of their gods, and then rulers, either living or departed or deified. (From Hawaiian History)

In 1830 Ka‘ahumanu, the Queen Regent, adopted Christianity and formally banned Hula. Some scholars believe this had as much to do with economics as religion. The Protestant religious morality and its famous work ethic were exploited in order to maintain control of the local working population. The burgeoning colonial agricultural enterprises needed cheap labor to be lucrative. Hula (as a marker of traditional Hawaiian culture) was considered to be “adversely affecting the willingness of the [Hawaiian people] to work.” According to an 1866 local editorial: “Hula … is only for pagans and the …. Hawaiian people are no longer pagan.” (The Hawaiian Journal of History, pg 43)

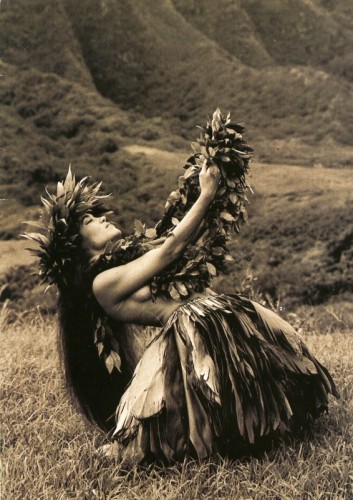

Photo Courtesy of Flickr’s Tom Simpson

Not long after, the “licentious” Hula became associated with prostitution and other forms of condemned sexual behavior. Regardless, the Hula was still practiced in private settings. There were clandestine schools that continued to pass down the traditions of the old ways. Hula dancers were sought after for private parties and events. The Hula dance was a sacred part of traditional Hawaiian culture and continued to thrive in any way that it could. In 1858, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser published the following:

It seems that the practice of hulas, or native dances, is becoming more universal every day. To the countenance and support of the government, through the columns of the Polynesian … it is clearly due to this retrograde movement of the nation towards heathenism. (The Hawaiian Journal of History, pg 38)

Photo courtesy of arielmurphy.blogspot.com

In 1886 King Kalakaua, the “merry monarch” lifted the ban which instantly revived the ancient dance. Although negative local press continued through the 1920s, Hula was once again being practiced publicly.

Over the next century, the Hawaiian Islands along with the rest of Polynesia became an increasingly popular vacation destination. As a result, the Hula dance found its place in world culture as an icon of paradise. A once sacred dance became a curiosity for waves of foreign tourists. As Hawaiian cities modernized Hula evolved once again from a simple curiosity to a genuine commodity.

Today there are generally two types of Hula: traditional and modern. Traditional “Kahiko” Hula is performed to chants and drums beats. It still clings to the movements of the original spiritual dance and rhythms of nature. The more common Modern “Auana” Hula incorporates elements from other cultures and includes a variety of instruments including song. Both forms are performed and celebrated at the yearly Hawaiian Merry Monarch Festival.

There is also something called “Hotel” Hula which is generally considered to be purely exploitative entertainment. Although it is a form of Auana, “hotel” hula is often criticized for its gratuitous emphasis on female sexuality in both movement and costuming. Interestingly, traditional Hula is also said to contain “unabashed expressions of sexuality” such as in the procreation dance (hula ma’i.) Moreover, in the pre-Missionary days the dance was performed by men and women who were scantily clad. However, unlike today’s “hotel” Hula, traditional Hula’s sexual elements are spiritual and sacred. As Sarah Neal writes, “the traditional dances were not necessarily sexualized, they were very sensual.”

“Female dancers of the Sandwich Islands” depicted by Louis Choris, the artist aboard the Russian ship ”Rurick”, which visited Hawai’i in 1816.

The evolution of Hula was clearly the result of Hawaiian cultural and religious change, colonialism, and modernization. The victim was the sacred meaning that lived at the heart of the Hula. This is not an altogether uncommon occurrence. When the sacred becomes a curiosity to outsiders it garners increased attention. The sacred then becomes culturally iconic. At some point, someone realizes that this icon can be monetized and turns it into a commodity. At that moment the sacred ceases to be sacred. It becomes a product – for better or worse.

Hawaiian history suggests that Hula was always used for more than a religious purpose. But at the same time it was always treated with reverence. Hula was more than a bobbling dancer on the dashboard of someone’s car or a pretty girl in a tourist poster for Honolulu.

There is a Hawaiian proverb that says, “Nana i ke kumu” (Translation: Pay attention to the source.) While it is socially acceptable to enjoy Hula in all its evolved forms, it is equally as important to acknowledge its origins. The Hula dance is a connection to that ancient Polynesian culture and the natural rhythms of the islands.

For me, Hula will never be the same.

Photo Courtesy of Andy Beal Photography

*As descriptors, the words “heathen” and “pagan” in lower case are used within a variety historical texts on the subject.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Yet another tale of how something sacred was destroyed by closed minded control freaks.

Thank you for the article. It was interesting to learn of the different styles of Hula. I especially like the point “Nana i ke kumu”. We could all probably learn from that.

Great article. my marriage ceremony was performed by a Hula master. In addition to being an oral tradition the polynesian tradition is also a somatic tradition. The stories and history of the people were stored in bodily movements that were passed down via the vehicle of Hula. Hula is a sacred vessel that contains the beliefs and history of the Hawaiian people. Thanks for giving attention to it! It is also interesting to see the vast differences in the sacred dances between different Polynesian peoples.

Thank you for sharing this important piece of Hawai’ian culture. Many are unaware of how many sacred indigenous cultural traditions have become transformed, and not in a positive way, due to colonialism.

As a major bellydance fan, I’m always so uncomfortable when someone tries to do hula fusion (aka “bellynesian”), because they never treat it as something sacred. For the ones I’ve seen, it’s just another context-free dance style to take bits and pieces from for fun. And if I hear an apologist say “Well, art evolves” one more time, I will scream. I swear it. Because being an artist does not absolve someone of fault for cultural appropriation and religious desecration.

And is there a reason why they would care?

I never thought much about Hula, but this in combination with another blog post on Sociological Images, has made me interested. Here is a link to that post – it also has some Youtube vids of traditional vs. modern/hotel dances. The traditional dances are beautiful, almost hypnotic.

http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2013/06/12/the-evolution-of-hula-traditional-contemporary-and-hotel/

One difference I note that in the SI-post, they say that Hula was mostly a men’s dance. Anyway, I also read somewhere (can’t find it in the post, so I guess it’s from somewhere else), that when looking at a Hula dance, ‘don’t focus on the dancer, focus on the dance’.

Yvonne, thanks for pointing out the gender issue. There is definitely a disagreement on who performed the dance originally – in pre-history. Some say men only and some say both. Most of the academic essays claim that the “men-only” theory is wrong and the dance was done predominantly by women. In my estimation, it was performed by both genders depending on the circumstances. Early Hawaiian culture had some strict rules about gender roles in society. It would make more sense to need both genders to perform the dance in restrictive settings.

Here is an interesting article about men dancing the hula . http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-201_162-550994.html

I agree with you, Heather. And thanks for the link!

Hula is a difficult subject to approach openly without also speaking of the (very elaborate) kapu, or taboo, system that goes with all matters of Hawaiian spirituality.

The survival of Hula is just one aspect of the impressive extent to which Hawaiians (and other Polynesians) have succeeded in preserving their ancient religious traditions despite the relentless efforts over many centuries to extirpate those traditions.

Even the missionaries themselves have often been forced to acknowledge the continued strength of these ancient traditions. A nice example of this is an essay written by the theologian Jean Charlot on “The Dialogue Between Christianity and Polynesian Religions” (link). The whole essay is worth close study, in my opinion, but the section on monotheism and polytheism is especially to be recommended.

Fascinating, FASCINATING article! Thank you for sharing! I would love to one day see a traditional dance in person. I once saw a very talented belly dancer perform and was enthralled by it. Could not take my eyes of her for one second. I wonder if it would be the same in this instance? 🙂