“One day earlier Benjamin would have got through without any trouble; one day later the people in Marseille would have known that for the time being it was impossible to pass through Spain. Only on that particular day was the catastrophe possible.” – Hannah Arendt

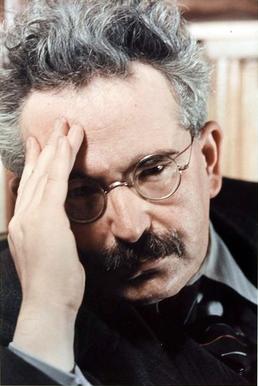

Walter Benjamin [Photo Credit: Gisela Freund]

At the time of his alleged suicide, Benjamin and his two companions were under police surveillance along with another group of refugees from France. They had arrived in Portbou earlier that evening after hiking over the Pyrenées from occupied France, only to learn that they were being denied entrance into Spain. They were to be deported back to France and handed over to the Vichy government the next day.

Despite assurances from members of the other refugee party that they could potentially bribe their way out of it, Benjamin took a fatal dose of morphine that night, after having been on the run for seven years. It was a dose that he had been carrying around since the burning of the Reichstag. This was seemingly an act of both desperation and defiance. He was not only more than aware of what his fate would be should he fall into Nazi hands, but he had also apparently decided long before that moment that he would choose death by his own hand over such a fate.

* * *

I am not much of a hiker, and I have never hiked a mountain before. I’m in decent enough shape considering that I don’t work out or engage in any type of regular strenuous activity, but I also struggle with chronic fatigue and nerve pain which often keeps me from outdoor activities. And I definitely knew on one level that the trail that I was so determined to hike was a bit out of my league in terms of experience.

But I also knew that Walter Benjamin was in much worse shape than either my friend Rhyd or I. And, every time I dwelt on the fact that he completed the route under the circumstances that he did, and in the poor physical condition that he was in, it served as ample justification for dismissing my own worries. The pull I was feeling to take the hike was strong and not fully of this earth, and I had recognized for many months that the trek was an essential part of our pilgrimage to Europe. We both recognized the importance of tracing his footsteps as a tribute to him, and that importance far outweighed any concerns that I had about my abilities.

At the time that Benjamin escaped from France over the Pyrenées, he was forty-eight years old and suffered from a heart condition, having been in delicate health since childhood. He had been living in poverty and exile throughout most of the 1930s, which had greatly exacerbated problems with both his physical and mental health. When he made his escape, he took with him a heavy briefcase that contained an unknown manuscript – one that he insisted was more important than his own life.

We packed much lighter than Walter Benjamin did, bringing only some food for lunch, two bottles of water, a half-empty bottle of Orangina, a sweatshirt, and our phones. I also took a small notebook and a solar charger, which I kept in a small side bag, while Rhyd carried the majority of our gear in his rucksack.

* * *

By summer 1940, Walter Benjamin had been in exile from his native Germany for seven years. He first fled to Paris in spring 1933, understanding the significance of the Reichstag fire long before most recognized what that event would mean for the future of Germany. As a Jew, a Marxist, and a cultural critic, he knew he was in danger for many reasons, and he sought refuge throughout France as well as briefly in Denmark with Bertolt Brecht. He was a heretic on the run, desperately trying to write and publish as much as he could while both his economic and physical livelihood fell into ever increasing danger.

In 1938, Germany revoked the citizenship status of Jewish citizens, and overnight Benjamin found himself to be a stateless man. Eventually the French caught up to him, and he was imprisoned in a French internment camp in 1939. After his release was secured with the assistance of friends in early 1940, he returned to Paris, where he stayed until French defenses were defeated by the Wehrmacht.

Benjamin then fled Paris for Lourdes the day before the Germans took the city. The subsequent armistice between Germany and Vichy France contained an extradition clause that denied exit visas for all German refugees in France and required the French to surrender anyone who had been granted asylum. Overnight, Benjamin was suddenly trapped in a country where he was a wanted man with no legal means of escape.

Knowing that he needed to leave France in order to save his life, he eventually left Lourdes for Marseille, where he managed to secure an entrance visa to the United States in August 1940. While in Marseille, he met up with his old friend Hannah Arendt and then reunited with Hans Fittko, who he had met the winter before when they had both been held at a French internment camp in Vernuche.

The mountains [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

After learning that Benjamin was trying to escape, Hans Fittko told him that the only potential route to safety was to make it to Spain without having to go through a border crossing, and then to cross Spain to Portugal and exit Portugal on a boat to the United States. Fittko then encouraged Benjamin to contact his wife Lisa, who had recently left Marseille for Port-Vendres on the border with Spain with the intention of finding a smuggling route over the mountains.

* * *

Every single website we had checked, including the official tourist site for the city of Portbou, stated that the hike was a 7 km, three-to-four hour trek. My instinct told me from the beginning that it was longer than that, and while my general rule is to trust my instinct, I also recognize (usually in hindsight) that there are times when I ignore that hunch for what later is revealed to be an important reason.

Looking back at this specific instance, the reason I ignored that hunch is very clear. Had I known how long the trek actually was, I likely wouldn’t have attempted it.

But having convinced myself at least on the surface that it was a 7 km hike based on the information that we found online, we planned for that amount of time and distance. We slept in that morning at our campsite near Perpignan and timed our travel so that we would arrive in Banyuls-sur-Mer around noon. Based on that schedule, we assumed that we would be in Portbou by four or five at the latest. We took just enough food for lunch and about three liters of water.

* * *

The route over the Pyrenées was a smuggling trail known as the Lister Route, named after Enrique Líster, a general in the Spanish Republican Army. Lister led his troops to safety over the Pyrenées to France at the end of the Spanish Civil War when Spain fell to the Fascists. While few knew of the route’s existence, one of the people who knew it well was Vincent Azéma, the mayor of Banyuls-sur-Mer, one of the first towns on the French side of the Pyrenées. Azéma was a socialist who had also been sympathetic toward the Republican cause in Spain.

A little over a year after Spain fell and Lister made his escape, the Vichy government took power in France. Azéma wanted to help those who were seeking to escape the Nazis, and his knowledge came in handy the day that Lisa Fittko showed up at his office seeking a route over the mountains. Like Walter Benjamin, Fittko was also a stateless Jew who was wanted by the Nazis. A dedicated anti-Fascist, Lisa and her husband Hans had also been on the run for years and had been working with the underground Resistance for much of that time. The Fittkos had also made their way down to Marseille not long after the Vichy government took power.

In September 1940, Lisa Fittko headed down to the border with Spain with the intention of securing a smuggling route across the Pyrénees. After only a few days in Port-Vendres, some dockworkers told her that the mayor of Banyuls-sur-Mer, Monsieur Azéma, would be able to help her find a route over the mountains. She went to see Azéma soon after, who discussed the route with her in great detail and gave her a hand-drawn map of the path.

* * *

I had never heard of Lisa Fittko until she died in early 2005. I had come across an article about her in the New York Times, which ran a story about her life and death and also mentioned Walter Benjamin’s tragic ending. I had heard of Benjamin before, but had never read his work, and it was that story in the Times which first prompted me to seek out his writings.

By that summer, I had immersed myself in his works, hunting down everything I could. It was the same summer that I ended up sharing my apartment with a young woman from southern France who was interning at a production company in Manhattan. The fact that she was from Perpignan, not far from Banyuls-sur-Mer, didn’t strike me as the least bit meaningful or synchronistic at the time. But all the same, that summer was dominated by two distinct perspectives: her observations and views of New York, and the work of Walter Benjamin.

Over the years, Benjamin’s work has undoubtedly influenced my thinking more significantly than that of any other writer, and nowadays I regard him not only as a profound thinker but also as both a prophet and an ancestor with whom I have forged a working relationship over time. And although the pull that I felt was much stronger overall than the individual parts that I could comprehend, the level of influence and relationship that I feel toward Benjamin was the primary reason why I felt the overwhelming need to trace the path of his fated escape path over the Lister Route during my pilgrimage to Europe.

It seemed fitting that my friend from Perpignan, who I hadn’t seen since that summer in New York eleven years earlier, was the one who kindly offered to drive us down to Banyuls-sur-Mer in the midst of transit and gas station strikes throughout France. She took us all the way to Puig del Mas, a neighborhood just south of Banyuls-sur-Mer, where the route actually began, and dropped us off on a side street that bordered the beginning of the mountains. We thanked her profusely and stumbled up the hill toward the end of the road.

* * *

On Sept. 24, 1940, Walter Benjamin knocked on Lisa Fittko’s door in Port-Vendres and told her that he had been sent by her husband and that he needed to escape to Spain.

Having met with Mayor Azéma only a few days earlier, Fittko quickly agreed to lead him over the mountains. She also agreed when he asked to take along two acquaintances who he had met in Marseille, a woman named Henny Gurland and her teenage son, who were also German refugees seeking to escape France. Fittko made it clear to Benjamin that it would be a strenuous climb, and that she did not know the route and that they would be taking a risk, but he seemed unconcerned. He stressed that to not make the attempt would be the “real risk.”

Later that day, Benjamin and Fittko left Port-Vendres for Banyuls-sur-Mer on foot, walking down back roads in order to avoid the growing police stops being conducted on both trains and auto routes. Fittko wanted to meet with Mayor Azéma again to go over the details of the route once more and to see if he had any additional advice or suggestions.

* * *

After Stéphanie dropped us off at Puig del Mas, we walked up the hill a bit but quickly realized that we couldn’t find the beginning of the route. I had downloaded a GPS map of the route onto my phone that morning, but it vanished from my screen and then refused to reload as we walked to the end of the road toward the vineyards.

Luckily, we saw a man exiting his car and walking up the hill. Figuring that he was a local, Rhyd asked him if he knew where the route was. The man was more than happy to walk us down the hill a bit, and then pointed us to the right and told us to look for a staircase.

We went down the staircase and through a narrow path, and found ourselves surrounded by vineyards.

We then walked for a few minutes up an easy path, and looking up at the trail before us, we decided to stop for lunch before tackling the steep terrain. We were surrounded by vineyards, some so old that the vines were literal trunks, bearing a much greater resemblance to dwarf trees than any type of vines I had ever seen before. I kept looking down at our food, and then up at the terraced vineyards, and it hit me halfway through our lunch that what we were eating, while quite unintentional, was very similar to the traditional meal that vineyard workers in the region were accustomed to eating – bread soaked in olive oil with some meat and cheese on the side.

After washing our food down with some water, we packed up our gear up again and headed upward through the vineyards.

* * *

When Walter Benjamin and Lisa Fittko sat down with Mayor Azéma that afternoon, he advised them to take a practice run in the daylight before actually hiking the full route. He recommended that they hike up past the vineyards and as far as the tree line, turn around and head back to town and check back in with him. Then, they could attempt the route in full the following day.

And so they set out on the route on the afternoon of September 24, only to learn quickly that the path was much steeper and more treacherous than Azéma had thought. Benjamin had brought a heavy briefcase with him, which Fittko offered to help him carry. When she asked him what was inside the briefcase and why he had brought it on a trial run, he told her that it contained his new manuscript and that he dare not risk being separated from it because its contents must be saved at all costs.

“It is more important than I am, more important than myself,” he told her.

It took them several hours to reach the tree line, and by the time they hit that point Benjamin was so fatigued and run down that he refused to turn back. After unsuccessfully trying to convince him to return to town, Fittko headed back to Banyuls-sur-Mer in order to prepare for the full hike the next day. Meanwhile, Walter Benjamin proceeded to spend the night, the last full night of his life, alone and exposed on the mountain at the base of the tree line with only his briefcase.

* * *

After Rhyd and I made it up past the first plot of vineyards, we came across an elderly couple hiking up the trail. They were equipped with hiking poles, which admittedly made me pause for a moment. Hiking poles? Do we need those too? What have we gotten ourselves into?

We walked behind them for a moment, until we came across an intersection in the paths. They were following the road, but another path went straight up into the mountains, and my instinct told me that the path straight up was the one we were supposed to take. And yet, we were without a map.

“Excuse me,” I asked them. “Do you know which path is the Chemin Walter Benjamin?”

He pointed to the path straight up, and then to the markings at the base of the path. “See the two black lines? Those are what you need to follow.”

[Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

It also didn’t take us long to realize that especially without a working GPS map, those trail markings were absolutely crucial when it came to staying on the path. As the path kept twisting and turning on our way up toward the top of the tree line, it occurred to me numerous times that if we hadn’t run into that couple we would have been hopelessly lost.

* * *

After leaving Walter Benjamin at the clearing on the mountain the night before, Lisa Fittko once again started up the trail before sunrise the next day with Henny Gurland and her son in tow. It took them about three hours or so to reach Benjamin, who was still lying down in the exact place where Fittko had left him the night before.

The party quickly discovered that Benjamin had a talent for navigation, and he expertly directed them, keeping them on the right path as they climbed further and further upward. Everyone took turns carrying Benjamin’s briefcase as they climbed toward the summit. On account of his heart condition, he insisted on taking a minute’s rest for every ten minutes walked.

Despite such a disciplined rest schedule, Benjamin stopped not long before the summit, insisting he couldn’t go any further, and both Fittko and Gurland literally dragged him up the incline to the next resting place not far from the top. A short time later, the group finally reached the summit.

It had taken them between four and five hours from the point of the clearing for Benjamin’s party to reach the summit, and seven to eight hours overall since Fittko, Gurland, and her son had left Banyuls-sur-Mer early that morning. But finally they had reached Spain.

* * *

A few hours after parting ways with the elderly couple, Rhyd and I finally spotted a sign that pointed toward the summit and stated the distance. I realized at that moment that the websites were all exactly half-right. It was 7 km and three to four hours to the summit at Querroig. But it would then likely be 7 km and another three to four hours to get back down and into Portbou.

It was now mid-afternoon, and the breeze and the shade of the cork-oaks made the hot sun bearable. As we continued to climb, a certain amount of diffused worry built up between us. Both time and our ability to stay hydrated were subtle but ever-growing concerns that we managed to communicate lightheartedly, but regularly, to each other without ever quite naming our exact thoughts for what they were.

We started to monitor our water supply, already halfway gone, taking smaller and more deliberately timed sips with an unspoken understanding that we would be up on the mountain much longer than we expected. We took extra care of ourselves; stopping for breaks under trees, continuously looking behind us as inspiration and relying on the visual power of the fact that the more that Banyuls-sur-Mer shrank in the field of vision behind us, the closer we were to the top.

And yet there were feelings of hopelessness at times, feelings that reverberated from our surroundings as much as they originated from within. And those feelings, as much as I tried to block them out, kept bringing me back to the figure whose escape path we were tracing.

The summit near Querroig. [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

After four hours or so we finally reached the summit. We took a few moments to rest and to take in the beauty of it all, but we then quickly began our trip down in order to try to make up for lost time.

* * *

Lisa Fittko had originally planned to leave Walter Benjamin and the others at the summit, as she did not have the proper paperwork and could not risk being caught on Spanish soil. But once she reached the top, she was concerned about their ability to navigate the treacherous downhill terrain. So she guided the three refugees down the narrow mountain paths.

Not long after they began their descent, they stumbled upon a greenish pool of water, obviously dirty and polluted. Walter Benjamin immediately bent over and stopped to drink, as the party had run out of water by that point.

“You can’t drink that,” she told him. “You could catch typhoid fever…”

“Yes, perhaps,” he replied. “But you must understand: the worst thing that could happen is that I might die of typhoid fever – after I have crossed the border. The Gestapo can no longer arrest me, and the manuscript will have reached safety. You must pardon me, please…”

And so he drank, and then they continued on downhill.

* * *

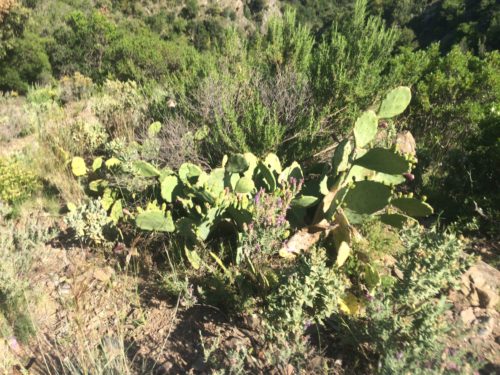

As we began our descent, I noticed that our surroundings were suddenly completely different than the terrain that we had been hiking for the previous four hours. The flora was different. The plants were different. Cork oaks and scotch broom had given way to cacti and succulents, and water could be heard rushing below. And the buzzing of bees was a consistent and strong presence throughout the entirety of our descent through the mountain brush. At times the bees were louder than our own voices, and while it faded in and out it served as a dominating chorus throughout the trek down to the road.

[Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

* * *

Lisa Fittko led the party downhill for another hour or so, until they finally reached a road at the end of a cliff-wall that led down toward a town below. Portbou was now directly in their sight and, at this point, Fittko bade them farewell, instructing the group to take the first train to Lisbon as soon as they had their entry stamps.

![A sigh pointing towards Portbou. [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/IMG_2801-500x300.jpg)

A sigh pointing towards Portbou. [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

It was there at the train station where they learned their fate. It was at this place where police told them that they were being denied entry into Spain and would be deported back to France the very next morning. They were put up at the Francia Hotel for the night under police surveillance, and Walter Benjamin allegedly committed suicide that night in his hotel room, believing that his luck had finally run out for good. His briefcase subsequently vanished.

* * *

It was at that same juncture between the path and the road where Lisa Fittko bade farewell to Walter Benjamin and his party, the same juncture where she had finally decided that they could make it the rest of the way on their own, that Rhyd and I briefly got lost.

I’m generally an adventurous sort that usually deals with being lost without much fear. But, at that point it was only a few hours until sunset; we had next to no water left, and we had already been on the mountain for nearly seven hours. We were not thinking clearly; our judgment clouded by the combination of fatigue, fear, and thirst. And, it was this lack of clear thinking that led to a few mistakes and a few moments of panic.

There was a fork in the road, one way headed slightly up and one way headed slightly down, both pointing in the general direction of Portbou. Those who know a thing or two about mountains probably would have deferred to common sense at that point: if you’re heading down, pick the road that goes down. But we are not mountain dwellers, nor regular hikers, and for the first time since we started, there wasn’t a waymarking sign or a trail blaze to be seen. So for some reason we decided that the road that headed upward was the way to go. And as we continued on, ever doubtful, that feeling of hopelessness once again crept in.

[Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

He pointed to another road below, stressing that even though it might technically be off the trail, the priority at that moment was to get off the mountain before sunset. I was doubtful but I agreed nonetheless, and we headed down that road only to discover within the next hour that it had actually put us right back on the trail, exactly where we needed to be in order to get to Portbou.

* * *

A few days after Lisa Fittko returned to Banyuls-sur-Mer, and before she had learned of Benjamin’s untimely fate, she was approached by Varian Fry of the Emergency Rescue Committee, who had heard of her success in smuggling Benjamin over the Pyrénees.

Fry and his associate had set up a legal French relief organization, the Centre Américain de Secours, with the intention of using it as a cover for smuggling Jews and other refugees out of France. Fry had both connections and funding, and wanted Fittko’s help in establishing a smuggling route that could potentially be lead by refugees themselves.

She agreed, and over the course of the next few years, Fittko and the Emergency Rescue Committee saved thousands of lives by leading folks over the Pyrenées via the Lister Route to Spain. Their efforts went down in history, and the Fittkos as well as Varian Fry are remembered to this day as some of the many heroes of the Resistance. The Fittkos finally fled France for Cuba in 1942 with the help of Varian Fry, and eventually settled in the United States.

And it wasn’t until almost forty years later, during a telephone conversation with Benjamin’s closest friend Gershom Scholem, that Lisa Fittko learned the fate of the mysterious briefcase that contained Benjamin’s final manuscript. She had always assumed that it had reached safe hands, especially given its importance, and was shocked and upset to learn that it had vanished.

* * *

Our original plan had been to reach Portbou by four or five in the afternoon at the latest, where we would then take a taxi to Cerbère, the very first town on the French side of the border, and then a train back to Perpignan where we were staying. The last train from Cerbère was a quarter past eight, and if we did not make it we would be stranded in either Portbou or Cerbère for the night.

A plaque near the train station in Portbou. [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

Signs of civilization where suddenly everywhere, from cars to dogs to a huge reservoir right below us. Without realizing it, due to our mutual state of light-headed and fatigued relief combined with the need to hurry, we followed the rest of Benjamin’s exact path into town without either map or sign as a guide. As we walked down the road toward town, we kept looking back at the mountain, watching as the fog quickly drew in. We had made it off the mountain just in time.

We continued through the tunnel, down the promenade, and to the train station where Benjamin and his party turned themselves in to the police. And while we were only seeking a taxi, not an entry visa, there was something in the moment, connected to the themes of hopelessness and escape, that lingered with meaning.

After a few minutes’ worth of location-based and linguistic stumbling, we finally hailed a cab to Cerbère and then caught the very last train back to Perpignan.

* * *

While the official story is that Walter Benjamin died by suicide, there is an alternate, much more recent theory of the last day of Benjamin’s life, which many dismiss as conspiracy theory. Yet, at the same time, it is surprisingly supported by a combination of evidence and inconsistencies. This theory claims that he was murdered by either the Gestapo or by agents working for Josef Stalin, who had learned of his escape plans and were determined not to allow him to leave Europe.

Both the Gestapo and Stalin had adequate reasons to want him dead. Not only was he a Jew and a Marxist attempting to escape the Nazis, but he had also apparently offended Stalin quite personally with his most recent and final work, “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Released in early 1940, “Theses” was a biting and influential critique of orthodox Marxism, and it was viewed by many as a betrayal of the tradition as well as a direct attack on the Soviet regime. There was also precedent for such an action on the part of Stalin. Leon Trotsky had been assassinated in Mexico City only a month earlier by an NKVD agent who was acting under direct orders from Stalin.

There are several oddities about his death that suggest that it was other than a suicide. First, theret was the suicide note itself, which many believe to be falsified because it had been written in French as opposed to his native German, and also contained inconsistencies regarding his location. And then there was the death certificate and related paperwork, which listed the cause of death as a stroke, not a drug overdose. There was also the fact that Benjamin was granted a Catholic burial in a Catholic cemetery, which would have been forbidden had he committed suicide. Finally, the fact that his briefcase disappeared also potentially points to a suspicious ending, especially given the degree to which he felt the need to keep its contents out of the hands of the Gestapo.

It is also notable that Portbou was a small, close-knit town and was rumored to be a Fascist stronghold with a reputation for hostility toward French and German refugees. Once Benjamin and his companions were detained, their presence in Portbou would have been anything but a secret, which created an ideal opportunity for agents of either Stalin or Hitler or anybody else for that matter who wished him dead.

How he truly died will always remain a mystery, as will the contents and the fate of the briefcase that disappeared after he perished. But his writings, his final days, and his life and death itself serve as a series of important lessons and reminders, not just of our past but our future possibilities and the potential we all hold to alter our fates through an understanding and analysis of what came before.

* * *

“Through his life can be read the violent unfolding of the twentieth century, which destroyed not only him, but millions of others. Yet his writings envision a world not condemned to repeat its mistakes, unlike the defeatist cosmology of a Blanqui; a world in which the political subject still has recourse to revolutionary praxis, unlike the disempowering theory of a Habermas. Benjamin’s writings tell of other possibilities, models for future thinking and acting, re-encounters with the past and proposals for what might yet be to come. Such are his important living remains.” – Esther Leslie

I had known for several years now that Lisa Fittko had written a memoir about her experiences smuggling refugees over the Pyrénees, but it wasn’t until we got off that mountain and back to Perpignan that I felt an overwhelming and sudden urge to read her book. It’s almost as though I had deliberately overlooked it on one level and, yet only in hindsight, had recognized this fact, sensing that having read it would ruin my adventure somehow. But after completing the route, taking in Fittko’s recollections seemed to be a crucial piece of the puzzle which was that experience. It is akin to seeking out a book for its details after having seen the film version. After sensing and experiencing what we had over the course of the seven hours over the mountains, I felt need to fill in the potential gaps and the questions in my mind.

I ordered the book online from France, had it shipped to my home in Portland, and started to read it immediately upon my return home nearly a month after completing the hike over the Pyrénees. I was immediately taken in by her recollections, and quite blown away by both her overall story as well as by a few similarities between her experience on the mountain and our own.

Among other things, had I read Fittko’s book beforehand and known that it would be a 15km hike that would take twice as long as I assumed it would, I likely would not have attempted it. And yet learning that they had also assumed a much shorter hike brought our experience in step with Fittko and Benjamin’s in an oddly synchronistic way. In her memoir, Fittko wrote of Mayor Azéma’s “elastic” understanding of time in terms of what “a few hours” actually meant, a tendency which she noted was common in mountain dwellers. Seventy-five years later, I had discovered the same tendency in those who authored the many websites that spoke of a three-to-four hour hike. In both cases, this tendency resulted in similar experiences and conditions in terms of the non-mountain dwellers who took such advice at face value, and then proceeded to trek over the mountains.

But much more so than matters of time and distance, Fittko describes a certain disposition, a certain determination and desperation, a certain way about Benjamin that he overwhelmingly exuded in her presence throughout his last days. The sentiments in her expression and emotion were so familiar that it was though I had read her words many times before.

For tucked into her words and descriptions were the identical sentiments and thoughts that I had taken from the mountain itself that day. In tracing Walter Benjamin’s final hours, in gaining that perspective as we followed his final path and in our mirrored experiences during that journey, I feel as though I somehow collided into his spirit directly and to this day the resonance of that collision is not only lingering but ever strengthening. In following the footsteps of and paying tribute to a prophet whose heresies tragically collided with fate, what came forth was a new level of understanding, connection, and Work.

[Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

* * *

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Brilliant writing about a compelling pilgrimage. My kind of Paganism! Mazel tov!

I am singularly unimpressed at the Spanish government’s pathetic and pitiful attempt to assuage it’s guilt and culpability in this incident. No matter how many signs it places on a trail will EVER do this. If the Spanish government wants forgiveness, then they need to dig deeper in their archives, discover and name the names of the culprits responsible for this man’s death and then name them publicly. So the world will always know, for all time, what utterly contemptible VERMIN they were and heap them with the derision they so richly deserve.

Beautiful.