Long before Ken Kesey was an author or a Merry Prankster, he was a farm boy from Springfield, Oregon, and the old hippies I often encounter never let me forget it.

While most outside of the Willamette Valley know Ken Kesey best for either his books or his psychedelic adventures, much of what is remembered about Kesey on a local level comes not from his years in the spotlight as a 60s counterculture figure, but from his role and actions as a generous, community-minded family man who spent the vast majority of his life in the Eugene/Springfield area. Kesey was a wrestling star at Springfield High School, a graduate of the University of Oregon and had married his high-school sweetheart prior to embarking on a decade-long adventure that began as a creative writing student at Stanford and culminated in a six-month sentence for marijuana possession in 1967. After his release from prison, Kesey returned to his family’s farm just outside of Springfield, where he lived until his death in the fall of 2001.

I’ve heard Kesey referred to jokingly as the “patron saint of Eugene”, and sometimes I feel that such a sentiment is more accurate than most care to believe. The spirit and influence of Ken Kesey is woven deeply into the counterculture tapestry of Eugene, through everything from the Oregon Country Fair to the legacy of the Grateful Dead, from the history of the Springfield Creamery to the still-continuing adventures of the Furthur bus. The most obvious reminder of and tribute to Kesey, however, is the plaza that bears his name, the only public plaza in downtown Eugene.

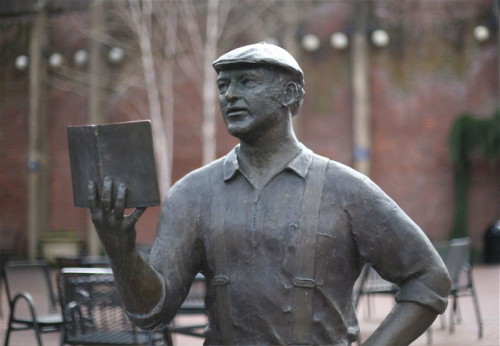

The plaza, set in a downtown corner lot formerly occupied by a building, has been a city-owned open space for at least forty years. Alternately called either “Kesey Square” or “Kesey Plaza”, the plaza was originally conceived as part of a pedestrian “downtown mall” that existed from the late ‘60s through the early ‘90s, and the area was dedicated to Kesey not long after his death. A statue of Ken Kesey titled “The Storyteller” was installed in the front of the plaza, which depicts Kesey sitting on a bench reading to his grandchildren, serving as a powerful reminder of Kesey’s legacy and influence in the heart of a city that was deeply shaped by his spirit.

Statue of Ken Kesey. Photo by Cacophony.

But despite its ideal location, and despite the energy and spirit of its namesake, the vibe of the plaza itself is stagnant and stuck. Kesey Square has always suffered as a place due to a combination of significant design flaws, a constantly shifting intent of usage, a reputation as a “problem” area, and the fact that it is the only public space in the commercial district. It’s obvious to most that these issues are interconnected and, in fact, feed directly into each other. But approaches taken by city officials to improve the area have always focused on the symptoms instead of the underlying causes and, as a result, the plaza has been the site of longstanding conflicts and disagreements between city officials, business owners, neighborhood residents and the regulars who hang out in the square.

As the only public plaza in a city that suffers from a significant lack of open space, Kesey Square is a magnet for those who have nowhere else to go. There are no publicly-owned benches anywhere throughout the downtown core, and sitting on the sidewalk can result in a citation, which leaves Kesey Square as the only public place where one can stop and sit, rest or relax. Consequently the plaza is primarily occupied by the poor and homeless, and the area is often strewn with backpacks, dogs, and other personal items, which is considered to be “unsightly” from the perspective of local businesses and certain residents. People gather around the statue, often dressing Kesey up with their own possessions, as they share food, play guitar, sell art or jewelry, or simply socialize.

Street youth in Kesey Square. Photo by Visitor7.

Kesey Square is also the only place in downtown Eugene where people are legally allowed to congregate in public at night. All local parks are under a 11pm curfew, and to linger in the parks even a few minutes after curfew is to risk arrest, which means that the crowd in the plaza at night is often even larger than the daytime crowd. Negative perceptions around the homeless lead many people, especially the barhopping crowd, to complain that the Kesey Square crowd makes them feel unsafe. And while such complaints historically haven’t been met with much action, the “downtown revitalization” efforts over the last decade or so have lead to increased strategies and tactics on the part of the city to displace those who regularly inhabit Kesey Square, but such actions have only added to pre-existing tensions while failing to chase away the targeted population.

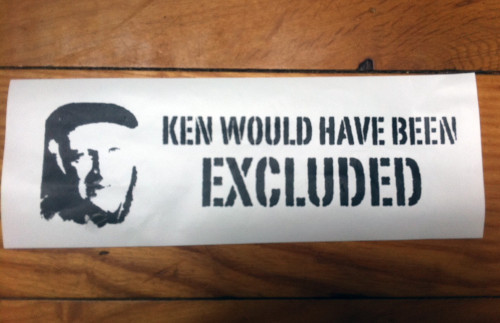

In 2008 the City of Eugene enacted and began to enforce a set of ordinances that were officially known as the “Downtown Public Safety Zone,” but more commonly referred to as the “exclusion laws.” The DPSZ ordinances allowed police to ban people from downtown who had been cited for certain “quality of life” offenses for up to 90 days, at their discretion, without requiring approval from a judge. The bans were immediate, meaning that the person was excluded from downtown before guilt or innocence had been determined in a court of law. Violation of the exclusion would result in an immediate arrest. The ordinances were controversial from the onset with the ACLU as well as community groups expressing concern that the discretionary aspect of the law would lead to widespread profiling and that the ability to ban someone from public space prior to their conviction was a violation of due process. The ordinance and its effects sharply divided the community with those concerned about human rights and discriminatory treatment positioned against those who felt that the homeless affected downtown business and were a threat to public safety.

The controversy steadily raged on with the issue being revisited regularly by the City Council in packed meeting halls. Over time, the city’s own data demonstrated that the ordinance was disproportionately being used against people who lacked a permanent address, while others who committed identical offenses were not being excluded. A homeless person smoking a joint in Kesey Square would lose their right to come downtown for three months, while a bar-goer a block away who had committed the same offense would only receive a citation or a warning. As the local economy went into further decline and the street population became larger and more visible, the police increased its usage of the DPSZ laws to the point where I would hear stories of exclusions on a regular basis. As enforcement increased, so did the time I was spending in Kesey Square, often sitting right next to Ken himself while witnessing the arrests of homeless people for violating the DPSZ.

Raising awareness about the DPSZ. Photo by Alley Valkyrie.

One afternoon, I was sitting next to the Kesey statue when a young man suddenly ran across the plaza, a man who I knew suffered from severe mental illness. He had been recently excluded under the DPSZ laws for “disorderly conduct” that occurred within the context of a psychotic episode. I watched as the police ran towards him and overtook him, as they tackled and arrested him for violating his exclusion and as I looked at the Kesey statue again the tragic irony of the situation suddenly struck me on a very deep level. People with mental illness were being banned from a plaza named after the author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and were being subdued and arrested directly in front of a statue of the author himself.

How did a plaza named after a counterculture hero become ground zero for socioeconomic conflict and class-based exclusion policies? Kesey himself would have been excluded under these laws, I thought to myself. He would have been sitting right here, smoking a joint while dressed like a hippie farmer, and they would have banned him from downtown for ninety days if they caught him. So much of this city’s reputation was built off the influence of Kesey and his kind, and I strongly felt that what was currently transpiring was anathema to what Kesey represented. As I sat there, this realization spread through me like a fire, almost as if the spirit of Kesey himself was fueling my rage. Kesey Square might be a troubled, dead space, but it was the commons all the same, and the person whose name is invoked in the title of this specific place would never have stood for what I was witnessing.

From that point on, I looked to Kesey as a spiritual guide of sorts, a wisdom-based reference point in my political navigations of the DPSZ issue. What would Ken do, I asked myself regularly. What did he stand for, what did he believe in? What is the intent of this place, what are the implications of excluding those who don’t “fit in” from the commons? How does one respect the needs of all and act in the best interest of the community in an ethical manner? I quoted and mentioned Kesey often, especially when pointing out the hypocritical gap between theory and practice in a municipality that has dubbed itself a “human rights city”. Ken would have been excluded, I reminded everyone.

Photo by Alley Valkyrie

Finally, after five years of advocacy, lobbying, protests, and consistent statistical evidence that made it undeniably clear that the DPSZ not only encouraged profiling but failed to significantly decrease crime or improve public safety, the DPSZ laws were finally sunsetted last fall, with city officials quietly acknowledging that the ordinance had been disproportionately used against the homeless and/or mentally ill. While on one hand it was a powerful example of a community successfully coming together to fight and eventually defeat an unjust ordinance, it did not feel like a victory in the traditional sense. When one enforcement tool is rescinded, another is always developed and enacted in its place, and we all knew that it was only a matter of time before yet another criminalization policy was enacted. The threat of exclusion may have been lifted, but the atmosphere of hostility remained and could literally be felt as one walked through Kesey Square.

And sure enough, earlier this month the City announced that it was considering a proposal to enact a 11pm curfew on Kesey Square, with the specific intent of displacing those who use the plaza at night. Such a curfew would essentially ban the homeless from downtown Eugene at night under threat of arrest, and both city officials and local business owners were very candid about the fact that ridding the downtown of the homeless at night was their intention. Excluding specific people may have been legally questionable in the past, but police expressed confidence that banning everyone from the square at night would not only pass legal muster, but was the only feasible solution for dealing with the “troublemakers” downtown.

After I heard the news, as the intent sank in and I started to come to terms with the battle ahead, my thoughts kept drifting back to Kesey himself. I have heard many times that Kesey was a solutions-oriented, common sense thinker, and I thought about such a mindset in contrast to the short-sighted madness that was directing the City’s intended actions. A few days later I walked down to Kesey Square, paced back and forth for the better part of an hour while wrestling with my thoughts, and as I finally looked up from the ground to the statue I noticed a sticker on an old VW bus that was stopped at the corner. The quote on the sticker was from Ken Kesey:

“You don’t lead by pointing and telling people some place to go. You lead by going to that place and making a case.”

I immediately refocused, realizing that the weeks ahead would be spent making that case. A case for the commons, for the importance of public space, for procedures and policies that help to bring people up, not kick them while they’re down, for better services for the homeless and mentally ill. A case against restricting people from public space, against criminalization policies that target the already disenfranchised, against prioritizing commercial interests over human rights. I believe in a better future for both Kesey Square and its inhabitants, and in the potential for a positive, vibrant public space that truly reflects the spirit and values of its namesake. I also believe that addressing the problems that lead to conflicts in spaces such as Kesey Square and crafting viable solutions is of a much greater benefit to the community than the current course that is being taken. Standing in the square, I looked at the statue once more and felt with certainty at that moment that making the case is exactly what Ken would have done.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

“Police expressed confidence that banning everyone from the square at night… was the only feasible solution for dealing with the ‘troublemakers’ downtown.” I was really floored by this statement. In other words, if we take away everyone’s freedom then we won’t have any troublemakers. Wow. Just, wow.

Rational, isn’t it?

If a part of the problem is that Kesey Square is the only public space in the commercial district, then part of the solution would be to create other public spaces nearby. Turf battles are less intense when there is more turf to go around.

I lived for decades in San Francisco and Berkeley, California, two cities that have large and visible homeless populations. Both places have park areas and plazas that are homeless hangouts and avoided by the general population, but they also have other public spaces where everybody goes. The people whose taxes maintain those amenities expect to get some benefit out of them, and they are right to expect that.

I’ve only been to downtown Eugene once. Speaking generally about urban design, even if the area is built up and land is expensive, temporary miniparks can be put onto vacant lots that are slated for future building; the public can be given access to rooftop terraces and private courtyards of commercial buildings. Streets that are ordinarily full of traffic can be closed to street traffic and turned into pedestrian malls for a day at a time, like the very successful Sunday Streets program in San Francisco, which was based on similar programs on the East Coast.

If there is only one public place where people can congregate, then as Alley Valkyrie writes, the people who have nowhere else to go are going to concentrate themselves in that area and set the tone of it. The problems this creates are somewhat similar to building large public housing developments exclusively for people who can’t afford to live anywhere else. Contemporary urban planning in San Francisco doesn’t concentrate housing for the poor in one place, but mingles the poor with the middle class by including below market rate apartments in every new apartment block built. The investors don’t like regulations that prevent them from maximizing their profits, but the tenants of various classes in the buildings get along well.

Everything in urban design is about money, although it doesn’t have to be entirely about money. If the ethos of a community doesn’t include the value of a common civic life, it won’t value sharing. Sharing means setting things up so that one group, whether it’s shoppers, tourists, artists, drug dealers, middle class families or the homeless, don’t dominate public space to the detriment of everyone else.

Ha ha! I was a loitering youth there back in the mid-80s and I didn’t even know it was called Kesey ANYTHING. Maybe that came after his death? Us kids didn’t have many places to go at night. And we all adored Kesey.